Nzinga was born into the royal family of Ndongo, a central West African Ambundu country, perhaps in 1583. She was descended from the Ndongo kingdom through her mother Kengela ka Nkombe. Nzingha's mother was her father Kilombo Kia Kasenda's favourite concubine.

From birth, she witnessed the kingdom's crippling struggles against the Portuguese Empire. In 1575, the Portuguese founded a commercial station in Luanda and at first maintained cordial ties with Ndongo.

But her opponents contested her legitimacy with several claims. Nzinga was told that she wasn't deserving of the throne because of her gender.

Furthermore, several Ndongan nobles perceived Nzingha's conciliatory attitude towards the Portuguese as a show of weakness, in contrast to the aggressive stance of earlier kings. They were particularly against the treaty's clause permitting Portuguese missionaries to enter Ndongo.

As the succession dispute intensified, Ndongo's relationship with Portugal became more complex. Nzingha sought to uphold the 1621 treaty with the Portuguese to regain Ndongo lands lost during her brother's wars.

However, tensions rose when de Sousa refused Nzingha's request for the return of Kijikos. A caste of slaves traditionally owned by Ndongan royalty, from Portuguese territory, as stipulated in the treaty.

He demanded Nzingha return escaped slaves, become a Portuguese vassal, and pay tribute. Nzingha refused.

Relations deteriorated further when de Sousa launched a campaign in late 1624 to compel Ndongo Sobas (local chiefs) to become Portuguese vassals.

Traditionally, sobas were loyal to the Ndongo ruler and provided essential support. By making the sobas vassals of Portugal, the Portuguese undermined Nzingha's authority as queen of Ndongo.

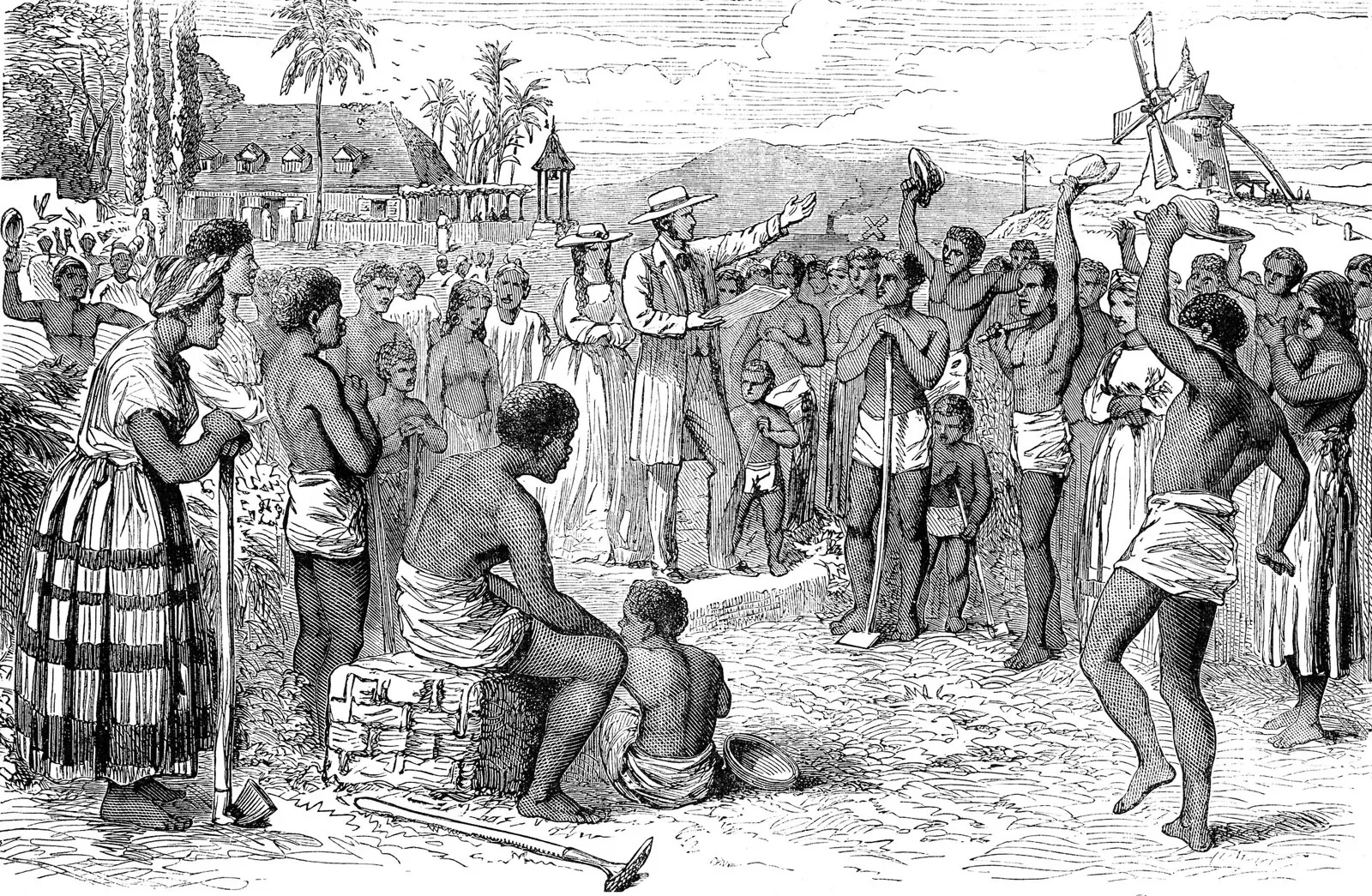

Nzinga undermined Portuguese colonial authority by sending messengers to Ndongo slaves, urging escape from plantations. She instructed them to join her kingdom. This tactic aimed to weaken the colony's income and workforce.

When the Portuguese complained about the escaped slaves, Nzinga stated that she would uphold her earlier treaty and return any escaped slaves. She also asserted that her kingdom had none to return.

This strategy proved successful, as many local leaders joined forces with Nzinga. This bolstered her position and alarmed the Portuguese, who feared an uprising led by Nzinga was imminent.

However, Nzinga's policies posed a threat to the income of both the Portuguese and Mbande nobles. Consequently, the Portuguese began to instigate rebellion within her kingdom.

In late 1625, they dispatched soldiers to support Hari a Kiluanje. He is a local leader who had severed ties with Nzinga due to his opposition to female rule and his own royal lineage.

When Nzinga attempted to crush Kiluanje's revolt, she suffered defeat. This defeat weakened her position and encouraged more nobles to rebel against her.

Nzinga appealed to the Portuguese to withdraw their support for Kiluanje, while she sought to gather more forces. However, the Portuguese saw through her tactics and eventually recognized Kiluanje as the king of Ndongo. This act led to the declaration of war against Nzinga in March 1626.

Faced with a Portuguese invasion, Nzinga mobilized her army and retreated to islands in the Kwanza River. Despite facing defeats in subsequent battles, she strategically abandoned most of her followers during a retreat. This diverted the Portuguese's attention towards recapturing escaped slaves rather than pursuing her army.

Meanwhile, the Portuguese encountered their own setback when Hari a Kiluanje succumbed to smallpox. This prompted the Portuguese to replace him with Ngola Hari as the new king. However, Ngola Hari was unpopular among the Ndongo people, who saw him as a puppet of the Portuguese.

This led to a division within Ndongo. The common people and lesser nobles supported Nzinga, while powerful nobles backed Ngola Hari and the Portuguese.

Nzinga made another effort at peace talks with the Portuguese in November 1627. She sent a delegate along with 400 slaves as a present. She was adamant that she was the legitimate queen of Ndongo. Nzinga also made it known that she was ready to submit to the Portuguese monarchy as a vassal and pay tribute if they acknowledged her claim to the throne.

The Portuguese, on the other hand, had rejected the offer. They also went ahead to behead her lead diplomat and counter-demanding that she give up her claim to the kingdom of Ndongo.

In addition, she was to retire from public life and submit to Ngola Hari as the legitimate king. These demands were within European diplomatic norms.

Nzinga experienced deep despair and sequestered herself in a chamber for a few weeks after receiving criticism from the Portuguese. During her time in the chamber, she also realised that other Ndongan nobles opposed her. Nevertheless, she surfaced, and a month later she launched a fresh effort to reestablish her connections in Ndongo.

Nzinga used Ngola Hari's political vulnerability as she regained strength, emphasising his lack of political background. Portuguese soldiers being his only reliance and lacking any of his own, Ngola Hari faced hatred from both his nobility and his Portuguese friends, a stark contrast to previous Ndongo monarchs.

In an attempt to delegitimize Nzinga's power, Ngola Hari and the Portuguese started a counter-propaganda campaign against her. However, this backfired as Nzinga gradually outwitted Ngola Hari in Ndongan politics.

In one famous incident, Nzinga challenged Ngola Hari to battle with her forces. She did that by sending him a collection of fetishes and threatening letters. Terrified, Hari sought Portuguese aid, crippling his image while bolstering Nzinga's.

She had to flee from the Portuguese army's advance as she was still unable to engage the Portuguese head-on in combat. She had a string of military setbacks. The most significant of which was a Portuguese ambush in which she managed to escape. She also lost half of her army, most of her officials, and both of her sisters.

Nzinga's forces suffered drastic decimation by the end of 1628, leaving her with only about 200 troops and effectively driving her from her kingdom.

Nzinga, expelled by the Portuguese, continued the resistance alongside her allies. Queen sought regional allies, shielding troops from Portuguese capture to bolster her army.

During this period, Kasanje, a formidable Imbangala warrior who had founded his kingdom on the Kwanza River, made contact with her. Ndongo's historical adversaries were Kasanje and the Imbangala. Kasanje had personally killed several of Nzinga's envoys.

In exchange for Nzinga marrying him and giving up her lunga. The Lunga is a big bell that Ndongan army captains used as a sign of their authority. Kasanje offered her an alliance and military assistance.

Nzinga married Kasanje after agreeing to these conditions and was welcomed into Imbangala culture. Swiftly acclimating to her new surroundings, the banished queen took up several Imbangala religious customs.

The complexities and scope of Imbangala rites and laws (Ijila) vary amongst sources (African, Western, modern, and contemporary).

Most accounts concur that Nzinga participated in the customary infanticidal (using an oil made from a slain infant, the maji a samba) and cannibalistic (drinking human blood in the cuia, or blood oath ceremony) initiation rites, prerequisites for female leadership in the highly militarized Imbangala society.

Part of the purpose of the rite was to avert a potential succession problem among the Imbangala. Nzinga merged Mbundu beliefs with Imbangala allies, preserving her heritage.

Historian Linda Heywood has pointed out that Nzinga's ingenuity was in fusing the Mbundu lineage with the Imbangalan's Central African military history and hierarchical organisation. This resulted in the creation of a brand-new, incredibly competent army.

She gave land, new slaves, titles to other exiled Ndongans, and freedom to runaway slaves to grow her population.

Although a subject of argument, Nzinga found herself politically aligned with the Imbangalans due to their emphasis on merit and religious fervor over kinship and ancestry. This alignment came after her disenfranchisement by the Mbundu-dominated Ndongo aristocracy.

Nzinga modelled her armies after the incredibly successful Imbangala warriors using her newfound power base. After rebuilding her army and successfully leading a guerilla battle against the Portuguese by 1631, a Jesuit priest who was residing in the Kongo at the time compared her to an Amazon queen and praised her leadership.

Nzinga invaded the neighbouring Kingdom of Matamba between 1631 and 1635. She took Mwongo Matamba [sv] prisoner and overthrew her in 1631.

Nzinga branded the defeated queen, sparing her life (Imbangala custom required execution) and claiming Mwongo's daughter as a warrior.

Having driven out the Matambans, Nzingha took the throne of Matamba and started to settle the area with exiled Ndongans, intending to use the kingdom as a base to wage a war to reclaim her homeland.

After Nzinga deposed the previous queen, Matamba, unlike her home Ndongo, had a long-standing cultural history of female leadership. This provided her with a more secure power foundation.

Once she had power over Matamba, Nzinga worked hard to increase the slave trade in her new kingdom. She used the money made from this trade to fuel her battles and take money away from the Portuguese.

She persisted in her fight against the Portuguese and their allies for the ensuing ten years, hoping to curtail each other's power and seize command of the slave trade.

Nzinga assumed more masculine characteristics throughout this decade. Donning clothes and titles appropriate for men. Queen, wielding female guards, demanded her male consorts dress feminine and call her "king."

She also imposed stringent chastity regulations on her female bodyguards and male councillors, as well as shared sleeping quarters at her court.

Nzinga's power had spread north and south of Matamba by the late 1630s. By using her might, she shut off other rulers from the Portuguese-controlled shore. This gave her control of portions of the Kwango River and the important regions that supplied slaves to the area.

Additionally, she increased the size of her domain to the north. Nzinga established diplomatic ties with the Dutch traders. The traders were becoming more active in the region as well as the Kingdom of the Kongo.

Along with this, Nzinga created a profitable slave trade with the Dutch. They could buy up to 13,000 slaves annually from Nzinga's kingdom.

She persisted in making sporadic peace proposals to the Portuguese, even going so far as to propose a military alliance—but only if they would back her return to Ndongo. Another issue that arose between the two was her refusal to be readmitted to the Christian religion.

Together with the Kingdom of Kongo, Dutch West India Company armies took control of Luanda in 1641. They exterminated the Portuguese and established the Loango-Angola administration.

After the Portuguese suffered a severe setback with the loss of Luanda, Nzinga promptly sent an embassy to the city under Dutch rule.

Nzinga, who was worried that her people's traditional northern opponents, the Kingdom of Kongo, were becoming too strong, asked for an instant alliance and promised to open the slave trade to them in the hopes of forming an Afro-Dutch coalition against the Portuguese.

Her offer of alliance was accepted by the Dutch. The Dutch promptly dispatched their ambassador and soldiers, some of whom accompanied their wives—to her court to support her in her conflict with the Portuguese.

The Portuguese governor made peace attempts with Nzinga when she was forced to retire to Massangano due to significant territory losses, but she turned them down. Kavanga, in the northern portion of Ndongo's old lands, became the capital of Nzingha.

The conquest of Luanda also made Nzingha's kingdom the leading, if transient, force in the area for the trade of slaves. This enabled her to establish a sizable war camp (Kilombo) with 80,000 (a number that included non-combatants) participants, comprising allies, mercenaries, runaway slaves, and her soldiers. Nzinga reclaimed Ndongo (1641-44) with military might, wealth, and fame.

Her aggressiveness, nevertheless, alarmed neighbouring African countries. In one notorious episode, she attacked Kongo's Wandu district, which had been rising up against the Kongolese monarch.

Nzinga refused to back down and annexed the territory to her realm even though these regions had never been a part of Ndongo; this severely infuriated Garcia II, the Kongolese monarch.

The Dutch mediated a peace deal to maintain their relationship with both Kongo and Nzinga, but tensions persisted between Nzinga and other local leaders.

Moreover, her former spouse and supporter, Kasanje, was concerned about her increasing influence in the area. Kasenje assembled a group of Imbangala chiefs to oppose Nzinga, taking over her territories in Matamba (although with minimal success). Her accomplishments gained her the backing of several Ndongan nobles by the middle of the 1640s.

Nzingha's military and economic power increased as a result of the nobility supporting her. By 1644, she saw Garcia II of the Kongo as her only political rival in the area, while the Portuguese saw her as their most formidable foe in Africa. Nzingha was able to gather more tribute (in the form of slaves), which she then sold to the Dutch in exchange for guns.

Nzinga decisively defeated the Portuguese army at the Battle of Ngoleme in 1644. After that, in 1646, she lost to the Portuguese at the Battle of Kavanga. This also saw the recapture of her sister Kambu and her archives, which showed her relationship with Kongo.

These records also indicated that Funji, her imprisoned sister, had corresponded covertly with Nzinga and had disclosed to her plans intended for the Portuguese. The sister was allegedly drowned by the Portuguese in the Kwanza River as a result of the woman's espionage.

At the Battle of Kombi in 1647, Nzinga defeated a Portuguese army. The Dutch reinforcements arriving in Luanda made this possible. After that, Nzinga besieged Massangano, the Portuguese capital, isolating the Portuguese there.

By 1648, Nzingha had taken control of much of her old kingdom. Her dominance over the slave trade had strengthened Matamba's position economically.

Even with these victories, the Allies' hold on Angola was shaky. Nzinga was unable to successfully breach the Portuguese defences at Massangano due to a lack of artillery, and the Dutch troops in Angola were undermined by political strife and events in Europe.

A Portuguese force under the command of Salvador Correia de Sá, the recently appointed governor, besieged Luanda in August 1648.

On August 24, 1648, the Dutch commander requested peace with the Portuguese and consented to leave Angola. This came after enduring a heavy Portuguese bombardment.

The peace between the Dutch and Portuguese<

Comments